Biology of the species

Posidonia plants have a characteristic life cycle , with clearly defined seasonal variations.

Autumn. Due to the first storms, common towards the end of the summer, the sea water begins to cool down and the plant loses its green leaves which during the preceding summer have been progressively coated by various species of animals and plants that use Posidonia as substrate. The tonnes of dead seaweed washed up on our beaches are produced through the action of these storms, and these seaweed leaves play an important role in the protection of the beaches. New leaves begin to sprout from the plant , using as energy the starch synthesized during the spring and summer months and which is stored in the rhizomes . The seaweed field now appears spacious and not luxuriant as it has lost the oldest leaves. The new leaves grow short and clean, without epibiont organisms (those that grow and live off the leavesí surface), and the field now acquires a healthy look.

This process constitutes the youthful stage and will last until the

month of March. During this time period, the leaves experience slow

growth.

It is in autumn that blooming takes place. In the Balearic Islands

the first flowers appear at the beginning of the month of October

and they first start to do so in the fields which are situated in

the shallowest waters, proceeding later to bloom in fields found under

deeper waters. It is possible to observe this phenomenon taking place

right through until the month of March, as not all fields bloom at

the same time. Although the exact mechanism that regulates flowering

is unknown, it seems evident that the depth and temperature of the

water exert a direct influence.

The Posidonia Flower

Winter. During this season, and coinciding with the

lowest temperatures of the year, the growth of the leaves which appeared

in autumn slows down to almost a standstill.

The process of flower blooming and slow growth of the leaves continues,

thanks to the starch accumulated in the rhizomes during the summer.

Towards the end of winter there appear the first fruits which are

not viable and will die off, necrotized by the low temperatures.

Spring.

During this season growth speeds up as the temperature of the water

increases. This is the period of maturity, the leaves grow very long

and the field acquires a luscious look of intense green for the leaves

are as yet sparsely coated by epibionte organisms.

The fruits which have been maturing since the end of the winter, germinate.

From the seeds come Posidonia sprouts of about 8-10 cms. , which float

about hovering over the sea bed trying to establish a foothold in

the substrate.

Summer.

During the hot months a large amount of organisms (hidrozoans, briozoans,

molluscs, etc.) attach themselves to the leaves, coating them progressively

until they totally cover them. These are the epibiont organisms. During

this process, the leaves turn a whitish colour due to the profusion

of organisms coating them. The growth of the leaves during this period

is minimal because of the crust that epibiont organisms form on the

leavesí surface and which prevents the leaves from carrying out the

photosynthesis, this will in turn eventually make the leaves turn

a brownish colour and die off. When the first storms arrive, the leaves

fall off, detaching themselves from the ligule.

During the summer the fields do not look very healthy due to the whitish

and brownish colours of the leaves.

Leaves actually fall off throughout the year, but they do so more

massively in the summer.

Sexual Reproduction

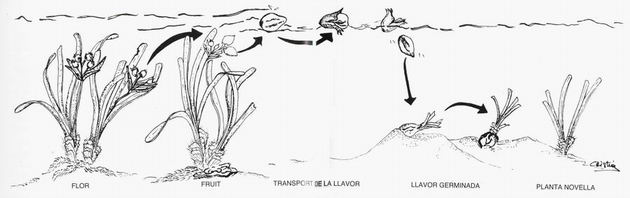

The plantís sexual reproduction is possible thanks to the flowers which hold the sexual masculine organs (stamens) and the feminine ones (pistils). Fertilization happens when the pollen from the stamens is transported by the marine currents and reaches the pistils. To make this possible the stamens produce filaments of viscose pollen that have serrated edges and are able to travel with the currents and reach the pistils of other plants. Once the plant has been fertilized the seeds will begin to form.

However, if we have seen that the fields are formed through the horizontal

expansion of the plants (vegetative reproduction), where is the sense

in, or what is the need for, a sexual reproduction? What are seeds

needed for if the plants can grow and spread without them?

The above reasoning coupled with the fact that the blooming of Posidonia

occurs infrequently, leads one to conclude that sexual reproduction

does not play a major role in the survival of Posidonia. Nothing could

be further from the truth: thanks to the process of seed formation,

new horizons that Posidonia cannot access through vegetative reproduction,

open up.

-

The sea currents transport the seeds and give Posidonia the possibility of propagating to distant places and establishing new colonies in new habitats.

-

The propagation of seeds allows the exchange of genes among Posidonia fields, and this is a vital factor in the evolution and survival of the plant. Determining genetic patterns has allowed scientists to demonstrate the genetic variety of oceanic Posidonia.

In this species there are also variations stemming from the different environmental conditions existing in places where the fields develop: cleaner or murkier waters, a greater or smaller degree of sedimentation, varying temperatures, etc.

These variations within the same species coupled with the possibility of genetic exchange, constitute the true evolutionary richness that allows the plant to adapt to slightly different habitats.

On the earth’s

surface, plants develop all shorts of ingenious mechanisms in order

to propagate their seeds: structures that allow seeds to fly in

the wind, animals that swallow the seeds, etc. What kind of resourcefulness

does Posidonia make use of in order to ensure that its seeds travel

in an aquatic environment?

If we dissect a fruit we will observe that the seed is coated in

a kind of meaty wall called pericarpium, which has the property

of giving the fruit a relatively low density. This allows the fruit,

once it has matured, to separate itself from the plant and, helped

by the waves, ascend to the surface of the water thanks to the floating

ability conferred on it by the pericarpium. For days it will travel

subject to the sea currents, until the pericarpium decomposes and

disintegrates thereby allowing the seed, which cannot float, to

fall to the sea bed. Once submerged, sprouting begins. In 2-3 weeks

the baby plant will be about 8 centimetres long and the leaves,

the stem and the roots will be clearly visible.

As in other reproductive processes, success is based on the production

of thousands of seeds because very few of them will find the optimum

breeding conditions for their development: the right degrees of

light, temperature, quality of the sea bed, etc. Most seeds will

washed up on the beaches or be lost in high seas.

The best environment for Posidonia to reach its optimum development is that of transparent waters. The more transparent the water is, the more the sun’s rays can penetrate the water and these rays are what provide the plant with the energy required to synthesise organic matter through the process of photosynthesis. Light is therefore one of the factors that regulate the presence of Posidonia.

The lowest range in which Posidonia can thrive is around 30-40 metres, although in extremely clear waters it can be found at a depth of up to 80 m. , and exceptionally, some fields exists at depths of 100 m. in certain areas around the Balearic Islands that have very transparent waters. Some authors believe that these still live deep fields are a vestige from the past when the level of the sea was lower than it is now. Density in these conditions is low.

The highest range in which Posidonia fields can settle is regulated by hydrodynamics, i.e. the rhythm of the waves. Waves break the plants up and stir the sea bed in such a way that they make it impossible for the plant to survive. In fields established in coves protected from sea waves, the plants can reach all the way up to the water’s surface, as happens for example at sa Nitja situated on the north coast of Minorca. Nevertheless, the most common shallowness in which fields can settle is that of 3-5 metres of water, where waves are not so strong as to pull plants up from the root.

As to the substrate, Posidonia can be found established in both soft ground of variable grain size ( fine grained sand, rough grained sand, silted sand, etc.) and in rocky ground. It needs only that the bed be of true ground containing a certain amount of organic matter. The optimum temperature for its development is that of between 15 and 20 degrees Celsius, and the plant does not tolerate variations in salinity.

Also, Posidonia fields thrive only in clean healthy

waters of a good environmental quality. This renders the plant very

vulnerable to human activity. Polluted waters make the fields recede

immediately. Therefore, the presence of Posidonia is a guarantee of

the quality of the water. The best quality seal that any coast line

may exhibit is the presence of healthy Posidonia fields, which are

an authentic guarantee—better than a flag of any sort.

Pollution of Sea Water

A large proportion

of waste produced by human activity ends up directly or indirectly

in the sea, and causes an impact of varying degrees on the Posidonia

fields. Empty bottles and discarded plastics and junk, dirty the

sea bed. Sediments coming from the coast (sewage emissions, waste

dumping) increase the murkiness of the water reducing the quantity

of light reaching the plants. Sewage and fertilizers cause an increase

in the level of nutrients and organic matter; the oxidation of the

same reduces the quantity of oxygen in the water and this in turn

can produce seriously harmful consequences for the fields.

-

Drag Fishing / Hauling Nets

Fishing with hauler ships and other similar fishing methods carried out over Posidonia fields (nowadays an illegal activity), open up clearings in the fields because they yank out large amounts of plant mass, many from the roots. These methods also increase the murkiness of the water by leaving the sediments floating about and thus reducing the quantity of sunlight that can reach the plants.

-

DredgingMany activities are carried out along coast lines, such as dredging for the construction of ports and piers, the extraction of sand and silt, etc., increasing the amount of particles in suspension which will later fall over the Posidonia fields blanketing them. Furthermore, dredging can dig up the plants’ roots leaving them exposed to waves that break them up.

-

The Casting of Anchors

PermanentThe anchor chains of permanent berths continuously drag over the Posidonia fields, they “till” the fields, cut the leaves and leaf masses, and eventually open up expanses of clearings in the fields.Occasional

In coves protected from sea waves, precisely those most popular for small boats and yachts, the mechanic movement of the anchors yanks out the leaves and rhizomes, sometimes pulling out whole Posidonia bushes.